| Back to Illustration by Russell Christian. Support Jim Knipfel in Patreon Purchase Jim Knipfel's books:

Copyright Jim Knipfel. All rights reserved. Back to |

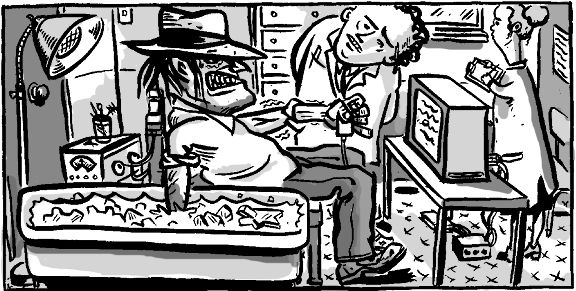

Slackjaw by Jim Knipfel Squelching the FeedbackIt wasn’t the first time I’d played the role of a scientific guinea pig. It wasn’t even the first time I’d taken part in a feedback experiment. The first time was some 20 years ago, at the Pain Research Center in Madison, WI, where doctors—at least I think they were doctors—were studying the uses of biofeedback in the treatment of people in extreme pain. This time was different. First of all, steel tubs full of ice water were not part of the experimental set up, and second, the feedback in question focused on brain waves, not muscle control. There was also no screaming involved this time.

I had taken part in a few minor neurofeedback experiments with this doctor a few months ago. He was the one who first noted that my alpha waves were unusually slow—pretty much akin to those found in your average lowland gorilla. In recent weeks the doctor had acquired some new state of the art neurofeedback equipment, and he asked if I’d be interested in trying it out. “Sure, why not?” I shrugged. I’ve always been curious about brains. Those earlier experiments involved only a small number of electrodes—one on each earlobe, and one or two plugged into my skull. The experiments themselves were simple. While the electrodes measured the waves in a tightly circumscribed portion of my brain, my job was, in one instance, to use Brain Power alone to control a computer generated tone. The tone flickered and stuttered, and I was supposed to try and make it continuous. In another experiment, likewise using only Brain Power, I attempted to control the levels reached by an animated colored bar on the computer screen. I wasn’t terribly good at either. On several occasions, I asked the doctor just what the hell neurofeedback could accomplish. “What would you like it to accomplish?” he replied. He then explained that it was still a fairly young field of research, and it wasn’t exactly clear yet what it could do, or why it did what it seemed to. But it did some weird things. It might help those pokey alpha waves of mine, he suggested, or even open up completely new neural pathways. Either sounded fine, I suppose, so long as there was no hypnotic and sinister mind control going on. I’d talked to my share of paranoid schizophrenics over the years, and believe you me, I knew I had to be careful.. While his initial set-up only used 3 or 4 electrodes at a time, his new equipment used close to 30, in order to simultaneously measure and record waves all over the brain. The new equipment also required the use of a high-tech skullcap. Electrodes? Skullcaps? Brains? Even as he described all of this to me, I began thinking that there was more than a little of the Mad Scientist involved here. He then told me that he’d only tried out the new equipment on one person so far—his wife. “I see…” I said. “Um…she hasn’t been clucking like a chicken ever since then, has she?” It was a serious question. He assured me she hadn’t, as he moved me into the chair in front of the enormous computer screen. He began separating a tangle of various cables and wires and gizmos, then tried to wrap a tape measure around my head. It didn’t fit, so he grabbed a longer tape measure. “60 centimeters,” he noted. “I hope I have a cap big enough to fit you.” (All my life I’ve been plagued by a large skull. Oh, how they laughed!) He got the computer warmed up and began sorting through his box of high tech skull caps. I, of course, was thinking of that Bugs Bunny cartoon. “Hmmm…” he said. The largest one he had at the moment was designed to fit heads between 55 and 59 centimeters in diameter. “Well,” he shrugged, “let’s give it a shot.” He attached an electrode to each earlobe and stuck one above each eyebrow. Then he picked up the skullcap, and the struggle began. He positioned the elastic cap atop my head and began tugging it down toward my shoulders to insure a snug fit. When he tugged it in the front, it popped up in the back. When he tried to yank the back down again, up came the front. Finally, after some sweat and struggle, a tenuous balance was reached—though I knew if I were to raise my eyebrows, I’d send it zinging toward the ceiling. In a flash, the doctor grabbed a thick elastic belt and wrapped it under my arms and around my chest, cinching it tight. I quietly began to worry some more. Then he grabbed the small straps which dangled from each earflap of my new headgear, and stretched those down to my chest, where he snapped each onto the belt, in a clear effort to affix it once and for all to my skull. I couldn’t move if I’d wanted to. “There,” he said, taking a step back. “Now you look like an astronaut.” Weird thing is, I was thinking exactly the same thing. Another weird thing is that the skullcap, with its built-in and properly-positioned electrodes, was actually designed to make the whole experimental set up faster and easier than doing it all by hand. The cap was dotted with pinholes, through which the necessary wires were to be stuck. Before that, though, came the conduction gel, which made sure that the electrode contacts were secure. Or something like that. The doctor filled a syringe with the gel, and began injecting it through each pinhole into my scalp. Once he’d hit all the electrodes (I think there are 28 or 29), he took the wires and poked them one by one through the holes, likewise into my scalp. When he was finished, all the wires spiraling out from my head were plugged into a small device on his desk, which in turn was plugged into the computer. He then hit a button and a cartoon image of a bald head appeared on the screen. The head was covered with dots of various colors. Each dot, he explained, representing a different electrode. The color told him how good the contact was at that particular point. Blue meant it was very good, red and yellow meant it wasn’t so good, and green meant it was passable. The goal before we could get down to some real neurofeedback action was to try and make all the dots blue. This involved either adding more conducting gel, or simply drilling the sharp little wires a little deeper into my skin. It was kind of like a game, if you think about it, which just happened to take place across my head. The doctor was a very nice and smart fellow, I liked him a great deal—but I began to wonder where in the hell he was going to find any other experimental subjects who’d put up with all this. “Okay,” he said finally, once all the dots on the cartoon head were blue, “Now…Just sit there quietly for a little bit.” He took a seat and stared at the computer screen/. Both of us seemed to have forgotten, if we were ever really all that aware to begin with, why, exactly, we were doing this. |